PFAS: From a “Wonder Chemical” to the Notorious “Forever Chemical”

A Complete Timeline for Packaging & Pharmaceutical Professionals

For decades, the packaging industry celebrated a group of chemicals that seemed almost magical. They repelled water, resisted grease, tolerated extreme heat, and lasted longer than nearly anything else we could manufacture.

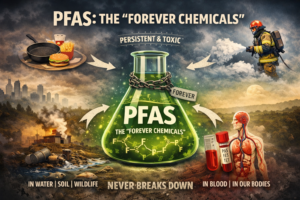

Those chemicals are PFAS — Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances.

Today, the same chemicals are at the center of global concern, strict regulations, and an industry-wide push toward PFAS-free packaging.

But how did we get here?

Let’s walk through the whole journey of PFAS, from discovery to being called “forever chemicals”, with a special lens on packaging and pharmaceutical applications.

The Accidental Discovery That Changed Material Science (1938)

The story begins not with regulation or controversy, but with accidental innovation.

In 1938, Roy J. Plunkett, a chemist at DuPont, was experimenting with gases used in refrigerants. During one experiment, he discovered a strange white, waxy substance that was:

- Extremely slippery

- Heat resistant

- Chemically inert

This substance was PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene) — later branded as Teflon.

At the time, no one could imagine that this discovery would launch an entire family of chemicals that would later be found everywhere on Earth.

The Rise of PFAS as Industrial Superstars (1940s–1960s)

During the 1940s and 1950s, PFAS entered industrial production, especially in the United States.

Why did industries love PFAS?

Because they offered something rare:

- Resistance to water

- Resistance to oil and grease

- Resistance to heat

- Resistance to chemicals

For packaging engineers, this was revolutionary.

Early applications included:

- Non-stick cookware

- Grease-resistant paper and board

- Water-repellent coatings

- Chemical-resistant seals and gaskets

In the 1950s and 1960s, 3M developed PFOS, while DuPont relied heavily on PFOA to manufacture fluoropolymers. These substances became common in:

- Food packaging

- Firefighting foams

- Textile coatings

- Electronics

- Pharmaceutical equipment and components

PFAS were not seen as dangerous — they were seen as perfect.

Quiet Warning Signs Behind Closed Doors (1960s–1970s)

While PFAS use was expanding rapidly, something important was happening quietly.

Internal studies conducted by NIEHS showed that:

- accumulated in human blood

- They did not break down easily

- Exposure levels increased over time

However, these findings largely remained internal and did not immediately reach regulators or the public.

From an industry perspective, PFAS were still considered safe when used as intended.

Scientists Discover PFAS Don’t Go Away

Independent researchers began detecting PFAS in unexpected places:

- Rivers and groundwater

- Soil

- Fish and wildlife

This was a turning point.

Scientists realized that PFAS were:

- Persistent (they do not degrade naturally)

- Mobile (they travel through water)

- Accumulating in living organisms

This persistence would later become the foundation of the term “forever chemicals.”

PFAS Found in Humans (1990s)

In the 1990s, research took a more alarming direction.

It was detected in:

- Human blood samples

- Breast milk

- Populations with no direct industrial exposure

Health researchers began linking exposure to:

- Liver damage

- Immune system suppression

- Developmental effects

- Increased cancer risk

At this point, PFAS were no longer just an environmental issue — they were a public health concern.

Public Awareness and Industry Shock (2000–2005)

The early 2000s marked a significant shift.

Investigations and lawsuits revealed:

- Drinking water contamination near PFAS manufacturing sites

- Long-term environmental pollution

- Prior internal knowledge

In 2000, 3M announced a phase-out of PFOS, signaling the first significant retreat from PFAS production.

For packaging professionals, this was the moment PFAS moved from being a performance advantage to a potential liability.

Regulation Begins — Slowly but Surely (2006–2015)

Regulators started responding:

- The US EPA launched PFAS stewardship programs

- PFOA began to be phased out

- Europe started tightening controls under REACH

However, regulation focused on individual PFAS rather than the entire PFAS family.

This led to a standard industry practice:

“Replace one with another.”

In hindsight, this only delayed the inevitable.

The Birth of the Term “Forever Chemicals” (2018)

In 2018, a term entered the public vocabulary that changed everything.

Dr. Joseph G. Allen, a researcher at Harvard University, used the phrase

“Forever Chemicals.”

Why did it resonate?

Because it explained in plain language:

- They do not break down

- They stay in the environment for decades

- They accumulate in the human body

The term transformed PFAS from a technical issue into a societal concern.

PFAS Are Everywhere (2019–2023)

Scientific studies confirmed what many feared:

- Found in rainwater

- Detected in Arctic ice

- Present in regions with no industrial activity

PFAS contamination was no longer local — it was global.

Governments responded with:

- Drinking water limits

- Product bans

- Environmental cleanup mandates

Today: PFAS as a Chemical Class (2024–Present)

We are now in a new era.

Regulators are moving away from regulating PFAS one by one. Instead, they are targeting PFAS as an entire class — nearly 10,000 chemicals.

What this means for packaging and pharma:

- “Essential use only” justification

- Strong push for PFAS-free packaging

- Increased scrutiny of:

- Extractables & leachables

- Supplier material declarations

- Sustainability claims

The question is no longer “Is PFAS useful?”

Simple Summary Timeline

| Period | Key Event |

|---|---|

| 1938 | First PFAS discovered (PTFE) |

| 1940s | Industrial use begins |

| 1950s–60s | Widespread commercial use |

| 1980s | Environmental persistence discovered |

| 1990s | Human health impacts identified |

| 2000s | Public awareness & lawsuits |

| 2018 | The term “Forever Chemicals” was popularized |

| 2020s | Global regulation & phase-out |

Final Thoughts from PackagingGURUji

PFAS were never created with bad intentions. They solved real engineering problems and supported innovation across industries — including pharmaceutical packaging.

But the very property that made them valuable — their permanence — is what makes them problematic today.

For packaging professionals, the future is clear:

- Understand where it still exists in your materials

- Engage suppliers early

- Invest in PFAS-free alternatives

- Stay ahead of regulation, not behind it

The story is a powerful reminder that performance alone is no longer enough.

Sustainability, safety, and responsibility now define good packaging design.

| Substance | Status |

|---|---|

| PFAS | Being regulated as a class |

| PFOA | Banned/restricted |

| PFOS | Banned globally |

| Fluoropolymers | Under review |